Acabei de ler, o livro do quase-filósofo, quase-auto-ajuda Alain de Botton, sobre a arquitetura dessa vez. O livro tem o mérito de todo livro do autor é divertido, abre uma curiosidade sobre pontos que influenciam a nossa vida diariamente e não nos damos conta.

Acabei de ler, o livro do quase-filósofo, quase-auto-ajuda Alain de Botton, sobre a arquitetura dessa vez. O livro tem o mérito de todo livro do autor é divertido, abre uma curiosidade sobre pontos que influenciam a nossa vida diariamente e não nos damos conta.De Botton acredita que o ambiente afeta as pessoas de tal modo que não seria exagero dizer que a arquitetura é capaz de estragar ou melhorar a vida afetiva ou profissional de alguém. Uma de suas teses é a de que o que buscamos numa obra de arquitetura não está tão longe do que procuramos num amigo. Ao construir uma casa ou decorar um cômodo, as pessoas querem mostrar quem são, lembrar de si próprias e ter sempre em mente como elas poderiam idealmente ser. O lar, portanto, não é um refúgio apenas físico, mas também psicológico, o guardião da identidade de seus habitantes. Seguindo esse raciocínio, o autor conclui nesta obra que quando alguém acha bonita determinada construção, é porque a arquitetura reflete os valores de quem a elogia. Pode até mesmo expor as idéias de um governo. Cada obra de arquitetura expõe uma visão de felicidade.

Uma opinião favorável do Washigton Post:

Building for Beauty

By JOHN MASSENGALE

Close to halfway through "The Architecture of Happiness," populist philosophe Alain de Botton finally gets to his central point, when he quotes Stendahl: "Beauty is the promise of happiness." For much of the 20th century, Modernism denied this connection between beauty and happiness. But in the 21st century, architects, artists, scholars and critics are returning to the subject. Mr. de Botton's book is an interesting and perhaps important addition to the debate over the emotional effect that our cities and buildings have on us.

Thinkers have begun approaching the subject from many directions. Christopher Alexander, an architect and mathematician, explores the intersection of beauty, the senses and feeling in his four-volume series "The Nature of Order." Israeli architect and professor Yodan Rofe walks people around his country's cities, recording their emotions as they stroll. The result: Specific locations routinely elicit certain emotions. In a book called "Emotional Design," computer science professor Donald Norman analyzes, as his subtitle has it, "Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things."

Now joining this burgeoning area of study is Mr. de Botton, the Swiss-born author of "How Proust Can Change Your Life" (1997), a fixture on British television who lives in London. Taking architecture seriously, he writes, means acknowledging the importance of our surroundings, even "conceding that we are inconveniently vulnerable to the colour of our wallpaper." The buildings we admire, he says, are ultimately those that refer, whether through materials, shapes or colors, to such positive qualities as friendliness, strength and intelligence.

Our sense of beauty and our understanding of the nature of a good life are intertwined, Mr. de Botton observes. We seek associations of peace in our bedrooms, metaphors for generosity and harmony in our chairs, and an air of honesty and forthrightness in our water faucets. We can be moved by a column that meets a roof with grace, by a Georgian doorway that demonstrates playfulness and courtesy in its fanlight window.

The buildings we create today often contradict these ideas of harmony, happiness and beauty. In 2001 in Berlin, the architect Daniel Libeskind made an aggressively angular and intentionally upsetting building for the Jewish Museum, to record what he calls the "displacement of the spirit" that took place during the Holocaust. That's appropriate for a Holocaust memorial, but Mr. Libeskind inappropriately used the same disturbing geometries for art museums in London and Denver.

Mr. de Botton registers the unhappy legacy of so many inhospitable structures and discusses at length why we need more optimistic buildings today, maintaining that one role of architecture is to supply the qualities missing in a particular society at a particular time. Ancient Greeks had no need to bring nature into their cities because nature was all around them, at close quarters. But in the 19th-century industrial era, when cities grew by leaps and bounds, we romanticized nature and created great urban retreats like New York's Central Park. Mr. de Botton cites the 18th-century German philosopher Friedrich Schiller, who thought his countrymen were in contact only with their flaws and thereby prone to melancholy and self-destructive poses. "Humanity has lost its dignity," he wrote, "but Art has rescued it and preserved it in significant stone." Schiller wanted, instead of art that affirmed society's flaws, an "absolute manifestation of potential," like "an escort descended from the world of the ideal."

We allow contemporary architects like Daniel Libeskind to do the opposite as they attempt to reflect the fragmentation and isolation of contemporary society. We allow this for two reasons. First, many of us expect to be confused or disturbed by modern buildings. We find them dispiriting, but we're assured by experts and the media that they're admirable structures. Second, we're told that architects like Mr. Libeskind are geniuses, so we think we must respect their work. In a Pavlovian way, we see an ugly building and think: "great."

"The Architecture of Happiness" rightly tells us to trust our senses and personal experience. The bad news is that Mr. de Botton sometimes makes his case in such an intellectualized way that he undermines the emotional resonance that he is seeking. Still, he brings a refreshing outsider's perspective to his subject. He closes by observing: "We owe it to the worms and the trees that the buildings we cover them with will stand as promises of the highest and most intelligent kinds of happiness." Stendhal would have agreed.

Mr. Massengale, an architect and urbanist, is the author, with Robert A.M. Stern and Gregory Gilmartin, of "New York 1900." He is a visiting critic at the University of Miami and the University of Notre Dame.

Uma opinião contra achada no Guardian:

A punch in the façade

Jonathan Glancey finds that, although beautifully packaged, Alain de Botton's latest book, The Architecture of Happiness, misses the point

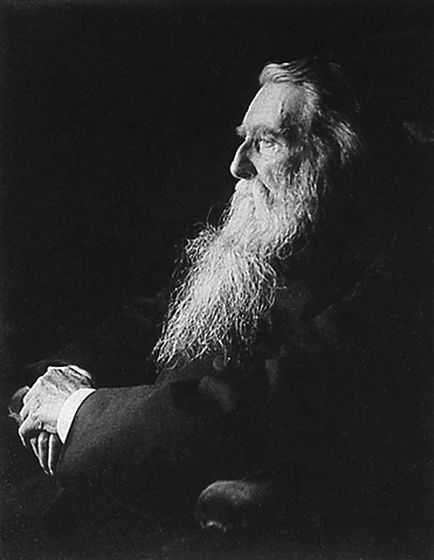

We meet John Ruskin early on in Alain de Botton's tantalising book on ideas of what makes a beautiful building, how architecture affects us and how architects might shape buildings that increase our chances of happiness. De Botton quotes him describing the basilica of St Mark's, Venice, as "a Book of Common Prayer, a vast illuminated missal, bound with alabaster instead of parchment, studded with porphyry pillars instead of jewels, and written within and without in letters of enamel and gold".

We meet John Ruskin early on in Alain de Botton's tantalising book on ideas of what makes a beautiful building, how architecture affects us and how architects might shape buildings that increase our chances of happiness. De Botton quotes him describing the basilica of St Mark's, Venice, as "a Book of Common Prayer, a vast illuminated missal, bound with alabaster instead of parchment, studded with porphyry pillars instead of jewels, and written within and without in letters of enamel and gold".Ruskin matters because he looked at architecture, and described it, with great honesty. There was no layer of intellectual gauze separating his eyes from the stones of Venice. He is a patron saint of sorts to every writer since who has tried to approach architecture honestly. In comparison, De Botton's musings feel somehow secondhand or one stage removed from the subject. Physically, this is a very pretty book, beautifully laid out and illustrated, but it is rather like a seductive box of deluxe Swiss chocolates, the contents of which prove to be stale and rather less substantial than the packaging.

De Botton does raise important, if familiar, questions concerning the quest for beauty in architecture, or its rejection or denial, yet from beginning to end, one is left with the feeling that he needs a choir of earlier authors to walk him across the daunting threshold of Architecture itself. These range from Epictetus, a first-century Stoic philosopher, and St Bernard of Clairveaux, to Sigmund Freud, Rainer Maria Rilke and Ludwig Wittgenstein who, famously, designed and built a rather difficult house for his sister, Gretl, in Vienna.

His approach to the subject is essentially literary - he appears to see buildings mostly through texts - so he is given to making extraordinary claims. "Architecture is perplexing ... in how inconsistent is its capacity to generate the happiness on which its claim to our attention is founded." I have looked long and hard at the bricks, stones and concrete of the Ziggurat of Ur, Albi Cathedral, Stuttgart railway station and even the pilgrimage chapel by Le Corbusier at Ronchamp, and found no promise of happiness in any of these great buildings. If architecture's capacity to generate happiness is inconsistent, this might be because happiness has rarely been the foundation of architecture.

His approach to the subject is essentially literary - he appears to see buildings mostly through texts - so he is given to making extraordinary claims. "Architecture is perplexing ... in how inconsistent is its capacity to generate the happiness on which its claim to our attention is founded." I have looked long and hard at the bricks, stones and concrete of the Ziggurat of Ur, Albi Cathedral, Stuttgart railway station and even the pilgrimage chapel by Le Corbusier at Ronchamp, and found no promise of happiness in any of these great buildings. If architecture's capacity to generate happiness is inconsistent, this might be because happiness has rarely been the foundation of architecture.My examples are monuments. What about houses? Here is De Botton: "Not only do beautiful houses falter as guarantors of happiness, they can also be accused of failing to improve the characters of those who live in them." But why should they? What is beautiful is not necessarily good. Many of the most beautiful houses in history, designed by architects, have been commissioned by monstrous or simply not very nice people. Unabashed, De Botton suggests that: "The objects we describe as beautiful are versions of the people we love."

De Botton appears to live a refined and rather precious world of his own, but one he imagines to be inhabited by other people - his "we" - who feel the same way about architecture and life as he does. "Touring cathedrals today", he observes, surprised by the numinous interior of Westminster Cathedral, "with cameras and guidebooks on hand, we experience something at odds with our practical secularism ..." Again, who are "we"? Roman Catholics, devout Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Bible-thumpers?

Significantly, when discussing the break-up of classical notions of architectural beauty in the late 18th century, citing the example of Stawberry Hill, Horace Walpole's playful Middlesex villa, De Botton lists "the factors which fostered the Gothic revival - greater historical awareness, improved transport links, a new clientele impatient for variety", yet fails to mention religion, and particularly the Catholic revival in England that spawned an architect, and crystal-clear writer, Augustus Welby Pugin, to whom we owe the appearance of the Palace of Westminster. And that of The Grange, a Kentish house that inspired a line of thinking that led to the Modern villas of Le Corbusier, who had read both Pugin and Ruskin, and whose own writings were as journalistically direct as a punch in the façade.

Significantly, when discussing the break-up of classical notions of architectural beauty in the late 18th century, citing the example of Stawberry Hill, Horace Walpole's playful Middlesex villa, De Botton lists "the factors which fostered the Gothic revival - greater historical awareness, improved transport links, a new clientele impatient for variety", yet fails to mention religion, and particularly the Catholic revival in England that spawned an architect, and crystal-clear writer, Augustus Welby Pugin, to whom we owe the appearance of the Palace of Westminster. And that of The Grange, a Kentish house that inspired a line of thinking that led to the Modern villas of Le Corbusier, who had read both Pugin and Ruskin, and whose own writings were as journalistically direct as a punch in the façade.Throughout, De Botton conflates literary ideas and values with those of architecture. Wedged into a window seat on a jet to Japan, he "turns to The Pleasure of Japanese Literature (1988) by the American scholar Donald Keene", who "observed that the Japanese sense of beauty ... has been dominated by a love of irregularity rather than symmetry, the impermanent rather than the eternal, and the simple rather than the ornate. The reason owes nothing to climate or genetics ... but is the result of the action of writers, painters and theorists who have actively shaped the sense of beauty of their nation." Yet even the most exquisite Japanese architecture has been shaped as much by the danger of earthquakes, a poverty of buildable space and by a historic paucity of building materials as by art.

De Botton has not really written a book about architecture. He never once discusses the importance of such dull, yet determining, matters as finance, property development, planning laws, politics, economic fluctuations, much less inventions such as the lift or steel or reinforced concrete or computer-aided design. He appears to believe that architects are still masters of their art, when increasingly they are cogs - burnished yet by the legacy of Borromini, Brunelleschi and all the greats - in a global machine for building in which beauty, and how Alain de Botton feels about it, is increasingly irrelevant.

· Jonathan Glancey's Eyewitness Companions: Architecture is published by Dorling Kindersley next month. To order The Architecture of Happiness for £15.99 with free UK p&p call Guardian book service on 0870 836 0875. guardian.co.uk/bookshop

![[The Architecture of Happiness]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PT-AD848_bk_bot_20061117150530.jpg)

![[Architect Thomas Leverton's fanlight window (1783) in London's Bedford Square]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PT-AD844_botton_20061117151418.jpg)